With the pressure of winter storms on the horizon, Pete Nielsen is struggling to make meaningful progress south to Florida, and then the boat steering fails

Boat steering failure on a lee shore: one sailor shares his experience

Towards the end of autumn 2018, I was trying to move Minx, my Pearson 39-2, south from Salem, Massachusetts to Jacksonville, Florida, writes Peter Neilsen.

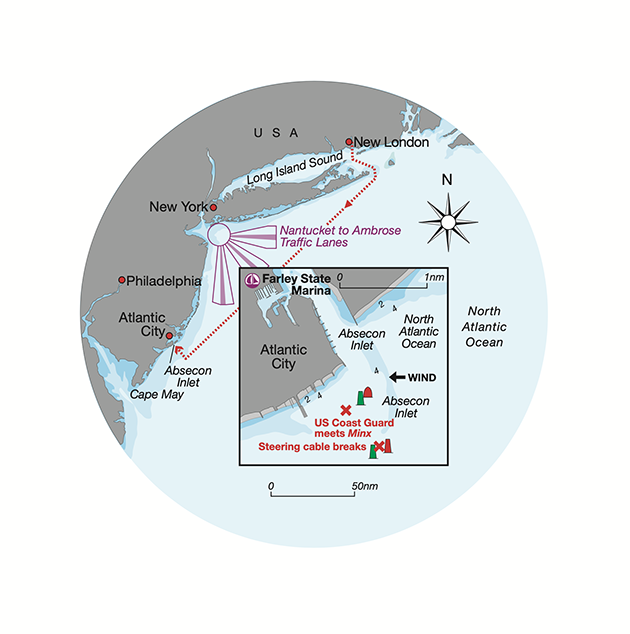

Things had not gone well. Two weeks after leaving, I had only covered 130 of the nearly 1,000-mile passage, getting as far as New London, Connecticut.

A never-ending series of nasty fronts had made it impractical to do more than port-hop, and during the few good weather windows I’d had work commitments that required internet and a non-pitching desk.

Winter on America’s East Coast is not to be trifled with –there’s a good reason insurance companies want boats out of the water by the end of October – and it was getting colder by the day.

So, by the time my friend Pat joined me for the remainder of the passage, I was feeling the pressure to get to Norfolk, Virginia, where we could enter the Intracoastal Waterway and avoid the offshore gales.

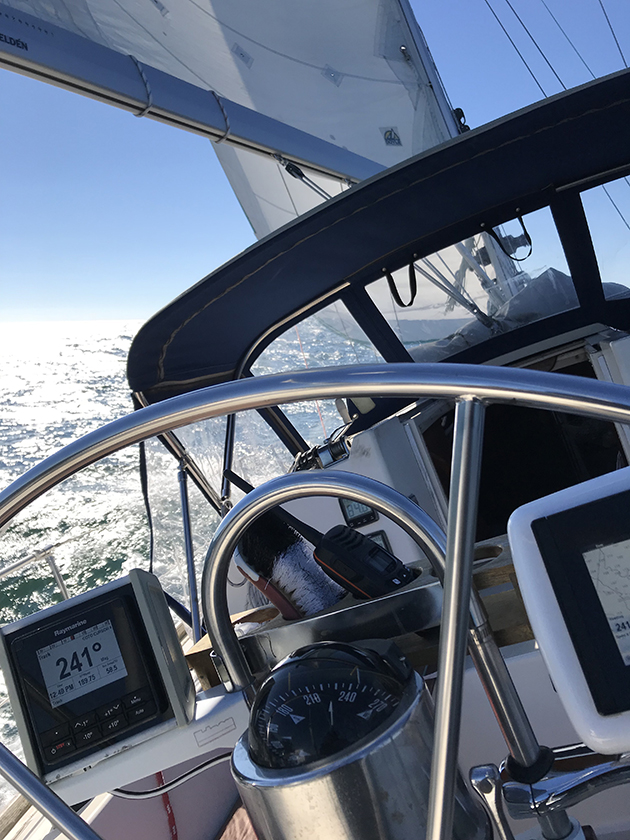

Sailing down the coast of Long Island. In hindsight, Peter should have sailed closer to land. Credit: Peter Nielsen

We left New London at the beginning of November, planning to sail outside Long Island for a 209-mile overnighter to Cape May.

The forecast predicted a northwesterly wind going south-east at 15-20 knots, which would give us a fast reach down the Long Island coast and past the shipping lanes leading out of New York.

We slipped the lines and enjoyed a few hours of fast reaching down the south of Long Island.

At 0200, the breeze was up to 18-20 knots and we put in the second reef. By 0400 it was blowing low 20s and the sea state was getting interesting.

We were bucketing along at 7-9 knots in the pitch-black and every so often a big growler would rear out of the murk and lay the old girl on her beam ends.

Peter Nielsen’s route. Credit: Maxine Heath

Soon we were getting gusts in the high 20s. Since we were going fast in the desired direction I wasn’t overly concerned.

At the 0400 watch change I found Pat looking extremely green and clutching a sick-bag; it was clear I was now solo and a change in plans was called for.

I decided to wait until daybreak to make the decision when we would be between Atlantic City and Cape May, some 35 miles further on.

By now the wind had backed to the east and kicked up a competing wave train. Short square-topped waves attacked from astern and from the beam; no more than 6-8 feet, not dangerous but completely unpredictable.

One would pass under us from our beam, lifting us and laying us over. The next would crash against the stern, skewing us to windward so the following wave would break near the bow and send a few buckets of warm spray back to the cockpit.

Peter Nielsen is a former assistant editor of Yachting Monthly and has sailed in Europe, the Mediterranean, the Caribbean, and along the East Coast of the USA. After retiring as editor of SAIL magazine in 2020, he refitted his 1987 Pearson 39-2, Minx, for long-term cruising and is currently sailing the Eastern and Western Caribbean.

Each time the stalwart autopilot brought us back on course.

With the genoa reefed halfway and two tucks in the main, I tried hard to think of a better sail combination, but since the boat and autopilot seemed to be happier than I was, I left things as they were and braced myself in the cockpit.

Long story short: it was probably the most unpleasant night at sea I have ever experienced. By the time the sun was rising I was fed up and had decided to run into Absecon Inlet, which leads to Atlantic City.

As the casinos of North America’s gambling capital gradually appeared out of the grey mist it became obvious that the shoaling waters were teasing the steep seas into washing machine mode.

I started the engine, rolled away the rest of the jib, and chicken-gybed – tacked instead of putting the stern through the wind – to put the breeze on our starboard quarter as we made the run in.

Minx refuelled for her next leg towards Florida. Credit: Peter Nielsen

I briefly contemplated dropping the mainsail, but it would have been too dangerous in that sea state, and I would need it if the engine failed.

By now it was a solid 25 knots true, and we were occasionally surfing down waves that hit maybe 10 feet.

The first channel markers appeared right on cue, then the second. And right as we passed between them, I felt the stern lift to the biggest sea yet and caught a glimpse of the speed log reading 14 knots as we slewed to starboard and hurtled towards the red can.

I put the wheel down hard, felt the rudder bite, and then there was a bang below my feet and the wheel spun freely in my hands.

Continues below…

Things to practise in harbour – fitting the emergency tiller

James Stevens explains which skills are best to perfect while you have plenty of time to do so. This week,…

Rudder failure on a lee shore. What do I do?

Would you know what to do if the rudder failed as you approached a lee shore? James Stevens answers your…