Berthing your boat while sailing the Baltic Sea requires some forethought, especially if you have never done it before. Rachael Sprot shares her top tips

The average yacht in the Baltic is smaller than those in the UK, with 30-35ft being the standard size for a family cruiser.

They’re often boats built in the 1970s or 1980s with a narrow beam and low freeboard, which means boat handling tends to rely on a push and shove rather than springs and pivot points.

Boats over 40ft are unusual although they can be accommodated. There is very little alongside berthing in the Baltic.

Box berths usually have wooden posts

Last time I was there, a Finnish skipper of a 36-footer berthed alongside a wall took out his seamanship manual to remind himself how to spring off against a cross wind.

He did it beautifully, there was no question of his seamanship, it was just a manoeuvre which is rarely required.

There are also very few cleats: the strong points onshore tend to be rings, so you can’t rely on lassoing the dock from the boat.

You either need to get a crew member close enough to feed a line through the ring or use a boathook with a special mooring clip on it to secure to.

Berthing in marinas is largely bows to, in either a ‘Y’ finger berth, a box berth or with a single stern buoy, all of which require nifty line handling from the crew.

They can be approached stern to if that’s your preference, which will certainly make leaving the next day a bit easier, in which case just reverse these instructions to set a bowline first and then attach a stern line to the dock.

- How to build a website with WordPress and what are the best plugins to use Building a website with WordPress is an excellent choice due to its versatility, ease of use, and a vast array of plugins that enhance functionality. Here’s a comprehensive guide to building a WordPress website, along with recommendations for the best plugins

- Top WordPress Plugins for Managing Ads and Monetizing Your Website Effectively: Why is Ads Management Important for Website Monetization? Strategic ad placement throughout the website enables publishers to maximize ad revenue while ensuring a positive user experience. The positioning of ads is critical in capturing users’ attention without being intrusive or disruptive. By understanding user behavior and preferences, publishers can make informed decisions regarding ad placement to ensure that the ads are relevant and engaging.

- Top Directory Plugins for WordPress to Create Professional Listings and Directories: If you are interested in establishing professional listings and directories on your WordPress website, the following information will be of value to you. This article will present the top directory plugins available for WordPress, which include GeoDirectory, Business Directory Plugin, Sabai Directory, Connections Business Directory, and Advanced Classifieds & Directory Pro.

- The Most Important Stages and Plugins for WordPress Website Development: Developing a WordPress website requires careful planning, execution, and optimisation to ensure it is functional, user-friendly, and effective. The process can be broken into key stages, and each stage benefits from specific plugins to enhance functionality and performance. Here’s a detailed guide to the most important stages of WordPress website development and the essential plugins for each stage.

- .org vs .com: A Top Guide to the Differences in Domain Extension

When you set up a website for a business or a non-profit organisation, you might think the most important part of the address is the actual name. But the domain extension (the bit that comes after the dot) is just as important for telling people what your site is all about. - The Best WordPress Plugins for Image Optimization to Improve Load Times and SEO. The pivotal element lies in image optimization. This discourse delves into the significance of image optimization for websites and its impact on load times. Furthermore, we will delve into the advantages of leveraging WordPress plugins for image optimization, such as streamlined optimization processes, enhanced SEO, expedited load times, and an enriched user experience.

- What is a data center or Internet data center? The term “data center” has become very common due to the role it plays in many of our daily activities. Most of the data we receive and send through our mobile phones, tablets and computers ends up stored in these data centers — which many people refer to as “the Cloud”, in a more generic way.

Y berths

Boat berthing in the Baltic: A Y-berth is where a single spar separates each boat. You can’t stand on a Y-berth spar, so you need another way to get you lines through a ring and back on board. Credit: Martin Leisborn

These wobbly structures look like finger berths but they definitely aren’t designed for a person to stand on (several British sailors have found this out the hard way), they merely present a strong point for attaching to and separating the berths.

It’s best to make sure you have lines and fenders rigged on both sides before coming in.

As you enter the berth a crew member standing at the widest point of the boat needs to attach the windward sternline or midships line, depending on your preference.

If double-handed, they can then give this to the helm before nipping ashore from the pulpit with the windward bowline.

You then need to set up the other lines. If the berth is very narrow then fenders may need to be abandoned.

Some Baltic yachts have a rubbing strake, but you can also drape a heavy line over the side to offer protection to the topsides.

Box berths

Ensure your beam will fit between the posts when box berthing. Have lines ready amidships to drop over the posts. Credit: Martin Leisborn

A box berth is similar to a Y berth, but instead of a floating boom between each slot there are two piles to squeeze between.

Again, the key is to secure the windward sternline from midships as you glide past, perhaps with a big bowline lassoed over the top of the post, or a line passed around it.

This way it can be pre-rigged for the helmsperson to pull in the slack. Once again the crew then need to step off with a windward bow line.

In this case fenders can be quite a hindrance as they can get hung up on the posts.

Some people prefer to have them lying on the side decks, ready to kick off once you’re through the gap, or rig them horizontally them with a sail tie at the bottom.

Stern buoy

Boat berthing: Threading a line through a buoy as you pass it isn’t as easy as it looks. A simple long metal hook is what many locals use. Credit: Martin Leisborn

Stern buoys are a more minimalist approach to berthing and often found in busy harbours.

They consist simply of a tall mooring buoy some way off the pontoon.

Again, a stern line needs to be attached on the way past, but bear in mind that stern buoys can be 20m or more from the dock, so it needs to be a long line which can be paid out.

For ease of departure the next day it helps to set this line to slip, in which case it may need to be very long and requires careful management to ensure that whatever slack is paid out doesn’t end up around the prop.

Continues below…

An expert guide to box berthing

Dutch boatbuilder Eeuwe Kooi has been box berthing all his life. He shows Chris Beeson how the pros do it

Could you moor in a box berth under sail?

With an onshore wind and little space to manoeuvre, how would you tackle getting into a tight box berth? James…

An expert’s guide to stern to mooring

If you charter in the Med, you’ll find yourself mooring stern to. Theo Stocker finds out how from Barrie Neilson…

>

Many local boats have a long metal hook to which they tie their mooring line, hook the buoy as they go past and then let go, the hook kept in place by gravity and line tension.

There’s usually only one stern buoy. It can be left to windward or leeward on approach and this will often depend on how the other yachts are lying.

Securing it on the leeward side of the boat will help keep the yacht square to the dock in a cross wind.

Have your fenders deployed as it’s likely you’ll lie on the yacht next door until you’ve got the fore and aft lines tensioned.

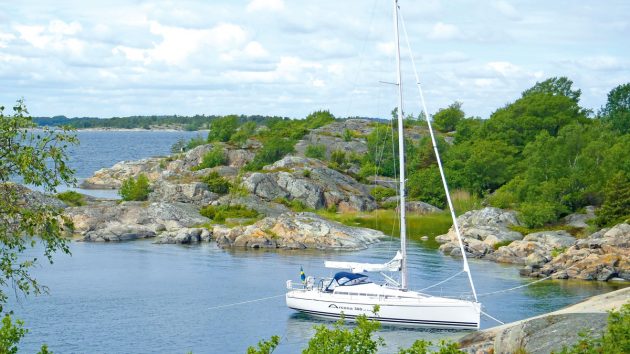

Rock moorings

The only thing cooler than screaming through the archipelagos under full sail, is tying up to a rock when you stop.

Rock mooring can be done in two ways: bows-to with a kedge anchor or, for the very brave, alongside.

Local knowledge, a decent pilot guide or reconnaissance by dinghy is required to identify suitable spots.

If approaching bows to, then the kedge needs to be deployed 2-3 boat lengths out.

Rock mooring is nerve wracking the first time you do it, but gives you access to some amazingly tranquil spots

The helm can pay out the warp whilst the bow team focus on getting a line ashore. In some places there are mooring eyes in the rocks, but a tree or sturdy boulder also work.

Snug up the kedge line to hold the bow off the rocks and drop back to give more clearance overnight.

Check the forecast for wind shifts – you need settled conditions or an offshore wind.

You don’t want to end up beam on to a strong wind, as you’ll be entirely reliant on the kedge holding.

Many Baltic boats have open pulpits or fold-down bow ladders to make stepping down onto the rock easier.

Alternatively, a small board lashed in place can make a useful step. Mooring alongside a rock is not for the faint-hearted. You need to be certain that the rock face is clean with no underwater protrusions.

You’ll also need to identify strong points to attach lines to before coming alongside.

Some people use climbers’ crevice hooks, but these damage the rocks and should be avoided if possible.

A couple of slim tyres are better than fenders as they’ll sink.

Start off with lunch stops only for your first time and anchor off for a good night’s sleep.

Kit list for boat berthing in the Baltic Sea

You don’t need tonnes of extra kit for a trip to the Baltic. Much of it can be picked up once you’re there.

Here’s a list of things the locals use routinely which might make life easier when boat berthing:

- A bow ladder. Hook-on ones are available if you don’t want to install one

- An easy-to-handle kedge anchor without moving parts, such as a Bruce

- Kedge anchor rode – a short stretch of chain, ideally stainless as it’s nicer to handle, and a long floating warp or webbing reel is ideal.

- A decent boathook

- Mooring hooks

- Rock wedges with eyes

Enjoyed reading Boat berthing: skills for sailing the Baltic Sea

A subscription to Yachting Monthly magazine costs around 40% less than the cover price.

Print and digital editions are available through Magazines Direct – where you can also find the latest deals.

YM is packed with information to help you get the most from your time on the water.

-

-

-

- Take your seamanship to the next level with tips, advice and skills from our experts

- Impartial in-depth reviews of the latest yachts and equipment

- Cruising guides to help you reach those dream destinations

-

-

Follow us on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.

The post Boat berthing skills for sailing the Baltic Sea appeared first on Yachting Monthly.